The October Diaries: Wait Until Dark

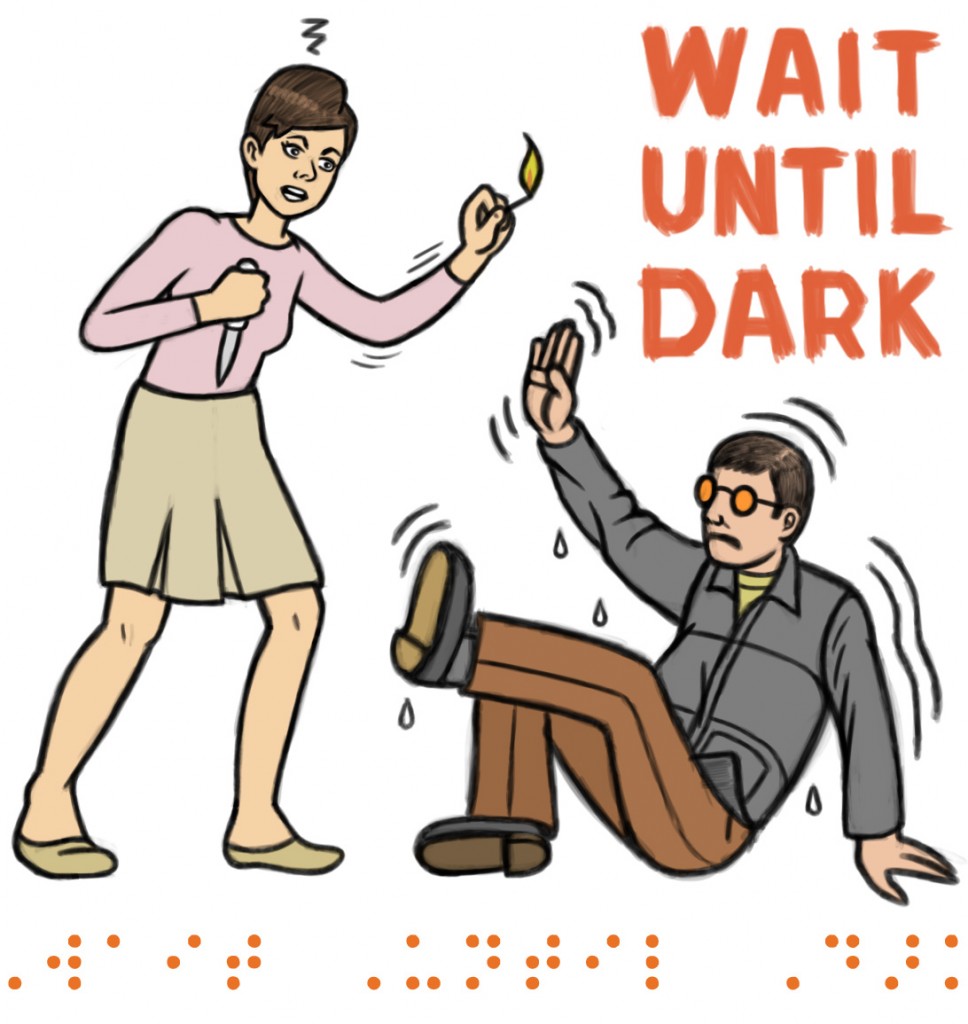

Illustration by Max Brown

Blurbs by Erin Roycroft, Sean & Christof

Illustration by Max Brown

Blurbs by Erin Roycroft, Sean & Christof—

October 11th, 2014:

Wait Until Dark

Year: 1967

Director:Â Terence Young

Vehicle: Amazon Rental

From IMDB:Â A recently blinded woman is terrorized by a trio of thugs while they search for a heroin stuffed doll they believe is in her apartment.

Erin’s Take:

I’m just going to say it: horror movies ain’t my thing. In fact, not only are they not my thing, I openly dislike the genre. Lucky for me, the Whitemans are no slouches when it comes to curating a movie night. Wait Until Dark, starring the infallible Audrey Hepburn and scored by Henry Mancini, it’s the perfect “horror†flick for a non-horror-watching weenie such as myself. I say “horror†because, aside from the last 15 minutes or so, Wait Until Dark is such a delight, it’s hard to tell what actually qualifies it as a horror film.

Most of the characters were three-dimensional in a way I’m not used to seeing in a horror film. Audrey plays Susy Hendrix, who was recently blinded in an accident. Probably the most compelling aspect of this film for me was Susy’s dual struggles with her blindness – which Hepburn flawlessly pulls off – while simultaneously being married to the most patronizing on-screen husband I think I’ve ever seen.

Through several plot twists, which I won’t get into here for brevity’s sake, we find out Susy was blinded only a year previously in an accident, after which she met Sam while she was trying to cross a busy street. Classic white knight moment, as Susy recalls it. In her words, he “rescued†her. Kind of hard to swallow, right?

But even harder to swallow was the way Sam took on the role of Susy’s Paternalistic Blindness Coach. In every one of his on-screen moments, Sam pushes Susy to do things for herself: to help him develop his photographs, to move things here and there, to defrost the freezer. Yes, he insists his blind wife defrost the freezer, and not just by unplugging it, but with fucking boiling water. In one moment of frustrated desperation, Susy asks, “Am I supposed to be the world’s champion blind lady?†Yes, Sam shouts back, she is dammit. I think he was supposed to be viewed as the white-knight, hero archetype, or at least that’s clearly how Susy views him, but his methods left my 2014 feminist sensibilities more than a little uncomfortable.

Thankfully, though, Sam doesn’t get much screen time. When Sam is called away for a bogus work assignment, three thugs turn up at the Hendrix’s apartment. The bulk of the film shows the thugs relentlessly fucking with vulnerable, blind Suzy in an attempt to recover a doll stuffed with heroine that was foisted upon Sam by a stranger at the airport, and which they believe is in the apartment. There are alter egos. There is a phone booth. There are covert signals. There is Audrey drama-ing the shit out of an all-out freak-out moment. There is Alan Arkin looking très creepy in some round John Lennon sunglasses. The action is all very fast – dare I say, dizzying – with lots of sleight-of-hand style movement of people and objects around the apartment.

Other delightful tidbits for me were: the evolution of Susy’s relationship with the neighbor girl, Gloria, who turns out to be an invaluable sidekick; the way that inanimate objects (the telephone, the doll, the safe, the blinds, the refrigerator, etc.) become characters in their own right; and the shriek-inducing shocker toward the end.

Sean’s Take:

This one had two sources of tension. The first was the plot. Its use of blindness as a variable for close-quarter thrills was very smart decision. The disparity between what we as an audience are shown and what Audrey Hepburn’s character can see leaves quite the impression. Often times danger lurks just outside of her perception and, as a member of a knowing audience, we can only squirm that patented October squirm.

The second tension derived from a more personal place. For a good portion of the runtime, this movie did not feel like a horror movie. It’s tough deciding what qualifies and what doesn’t. I was nervous we had maybe picked a film that, while being great, might not have enough of that ineffable bloodletting to pass the scrutiny of our living room council (disqualification as horror would mean we’d have to watch a different one afterward as comeuppance and, as much as we love horror, this process doesn’t leave many available hours for 9-5 schmucks like us and we cherish what scraps we get). Thankfully, the body count rose by the end and horror did indeed make a cameo appearance.

The cast was excellent. Hepburn was as charming as her legend warns and she pulled off a very tricky role, balancing multiple sets of emotions, sometimes within the same moment (not to mention the whole playing-blind thing). Seeing baby-faced Alan Arkin, as this movie’s chief creepo, was a particular delight. Playing a beatnik-baddie, he looks younger than I do right now and Alan Arkin should never be younger than anybody. Richard Crenna and Jack Weston were fantastic to round out the cast.

This one deserves a full-on essay, one espousing the breathless telling of a complicated and stagey (one chief location) tale. Hepburn’s husband also deserves some examining. He pushes her hard to overcome the limitations of her blindness and she wears from the effort. At one point, exasperated, she yells, “Do I have to be the world champion blind lady?†He curtly responds, “Yes.â€

There’s a scene near the end where he makes her walk toward him one more time. He doesn’t go to her, despite what danger has transpired. As he tests her, to see if she can make her way across the room without trouble, he has that aww-look-she-can-do-it-now glint of pride in his eyes and the moment is played as emotional and touching. The scene suggests the disciplined approach he took in his care for her blindness benefited her during her ordeal. This moment feels sour instead of sweet. He just comes off as a dick for instigating another bout of petty “testing†when she just outlasted a room full of heavies while he was off being fully-sighted somewhere safe.

That gripe aside, one owed to the prevailing mindset of the generation the play and film were born from, this movie was great. It was the type of suspense that reminds us that Hitchcock didn’t have a monopoly on suspense afterall. It might not be the best horror movie of the month, but it might be the best movie.

Suzy (Audrey Hepburn)Â clutching the balusters like the bars of a prison.Christof’s Take:

This is my probably favorite movie of the month – rich Technicolor-dyed images, interesting and complex performances, pretty and nightmarish music by Henry Mancini, a compelling story centered around a primary elaborate set (the film is based on a play, and it delightfully comes across that way) – but what worried me going into it was a question that took a long time to answer, “Is this horror? Does this count?†It felt like a lot could be riding on this since it would be embarrassing to have my favorite horror movie of the month not actually qualify as horror.

It is more of a Hitchcockian crime-drama serving as a vehicle for charm and suspense – a vehicle with a well-built engine. AÂ newly-blinded woman, Suzy (played by Audrey Hepburn with bottomless grace), is unknowingly the gate-keeper to a highly sought-after McGuffin, a doll-stuffed with heroine that her bizarrely demanding husband was conned into holding onto for someone else.

There are three men looking for the doll, led by super-manipulator/hepcat, Roat (played by a young, spectacular Alan Arkin). They implement a complicated set of ruses by entering Suzy’s apartment under false and seemingly harmless pretenses. They end up performing a sort of radio play for her so she can put together the fictional puzzle-pieces of a story they’ve constructed and offer up the doll without ever knowing what she’s giving away. (Some amazing acting here – actors playing criminals who are acting like innocent people, conveying what they need to with their voices while their facial expressions are free to reveal the truth behind the lies they speak.)

This is where I first started to attempt to justify this as horror, thinking of it as a different kind of psychological horror film. Not the Lynchian kind where a character’s psyche starts to unravel into dark surrealism. Instead, it’s sort of like a psychological slasher film. The criminals in-depth lies and manipulations are the knife, and her psyche is the victim. Or at least that’s what I told myself to try to get my horror brain to shut up and enjoy the movie.

Of course, the a story cannot go as characters plan, so shee starts to put some of the actual puzzle-pieces together, suspecting something is amiss. Soon, she begins acting and lying too, and this is when she first begins to fight back, holding onto what control she can have over a situation that would seemingly leave her hopelessly imprisoned by circumstance. (See above image.)

By the end, I wouldn’t require my previous justifications about the genre, as her resistance to the convoluted lies leads to them taking more drastic measures, which are much more in the realm of fear. The horror becomes very apparent on Hepburn’s face as she reacts and struggles to hold onto any control in a situation where desperate criminals have the upper hand. There is a particularly icky and horrific scene where Roat uses a scarf to torture Suzy’s sense of security via her tactile awareness as she screams and cries, not knowing what is touching her and never knowing where she’ll be touched next. Hepburn’s performance is a feat.

The movie, which didn’t feel like horror at first, ended up winning the Trophy for Biggest Scare of the Month. This particular moment I’ll leave nameless and without description, but it definitely gave me a big jump, amplified by watching others in the room jump and hearing our collective vocalized startle-sounds.

Overall, the suspense-horror of the end was well ushered along by the pitchy, wobbly piano score by Mancini, pulsing out a slow, tense mood of unreal dread.

With almost no complaints, there is kind of a biggie I need to address. I was disappointed in the husband character. He is insistent on her doing things by herself, which is great from one aspect but also contradictory, creating independence founded on dependence. I wanted him to be less of a short-sighted control freak (even if his control is what enables her control, and maybe partly because of the shitty implications of that).

Early on, this is fine. It’s wonderful to have such intense flaws in characters. To have him trying to sculpt her and to have her be needy and desperate for positive reinforcement from him is a great way to start a story. Characters should be in need of change at the beginning of a story. Their marriage is a unique situation, and people don’t usually react as they should in unique situations.

But at the end, after all she’s been through, he arrives at the apartment and tells her to come to him. “I’m over here,†he says, officially encouraging her while she’s still understandably distraught. It comes off as needlessly making a dog do one last trick as he urges her to come to him, that she can do it on her own.

Yeah, we know she can, ya jerk.

What I (and many in the room) wanted was for Suzy to literally stand her ground and reply, “I’m over here,†and make him come to her. This would be the ending to justify the beginning, but no such luck.

I think this would have been a more symbolically potent ending, and without it, the scene plays like it thinks it has accomplished interesting growth in an emotional territory, but really has left our characters nearly arc-less in the aftermath.

But for the genre, these characters are some of the most well-rounded ones we’ve seen this month. They are complex enough sidestep quite a bit of easy reduction in most cases, and this is impressive when you consider the film came out 47 years ago. Keeping this in mind, along with how charming, lovely, and frightening the motion picture is, it is easy to look past this problem and appreciate the movie for what it ended up being instead of what I felt it should have been.

Very grateful to Audrey Hepburn for classing this month up.